It was a cold and drizzly day when we visited Pieve Santo Stefano, a town some 15 kms north of Anghiari, near the source of the Tiber, which runs right through the middle of the town. Pieve is close to the birthplaces of both Michelangelo and Piero della Francesca. It was almost completely destroyed by the retreating German army during the second world war, and the non-descript postwar buildings contributed to a bleakness about the day of our visit. By contrast, what awaited us was yet another experience of the gracious hospitality we had been shown while staying in this part of Tuscany.

We had come to Pieve to visit the Archivio Diaristico Nazionale (the national diary archives of Italy). The main building in which the archives are located is one of the few that survived the war. The others include a market loggia, next to the ‘town hall’ which houses the archives, and a nearby church with a beautiful terracotta from the Andrea Della Robbia school. (There is also one of these terracottas in the archives: what a miracle that these survived.) Natalia Cangi, the busy director of the archives, had kindly set aside a couple of hours to show us the archives’ Piccolo Museo. And what a treat it was.

The archives, along with an annual prize for an Italian, or bilingual, diary, were established in 1984, with the aim of collecting the diaries, memories and letters of ordinary people. It currently holds around 7,500 pieces, and is used as a resource for students and scholars in sociology, anthropology, history and linguistics. Significantly, a major concern has been that these writings become part of a ‘living memory’, rather than being ‘closed away in a museum’. This principle has been wonderfully realised in the design of the piccolo museo, and we could see why schoolchildren, for example, would find it as engaging as they apparently do.

The museum is indeed small, with just four rooms, each with a different focus, designed with great thought and care. You want to pause; there is no impulse to rush on to the next room. The first room plays with the tension between ‘memories shut away in a drawer’ and ‘living memory’. It simply consists of a wall of drawers. Inside each one is a copy of a diary that can be read while it is being spoken by an actor. There is nothing clichéd about this: it is thoroughly professional and engaging, and you find yourself wanting to open more and more drawers. You are surrounded by living voices.

The second room is devoted to diaries and letters from the second world war, many of which are testimony to the tragic conflict within families and communities that resulted from Italy’s role as an ally of Germany in the war. The third room focusses on the family history and writings of one 20th century ‘semi-illiterate’ Sicilian man, Vincenzo Rabito. A story of a century comes to life through his story; and the room is carefully designed so that you find yourself participating in this life.

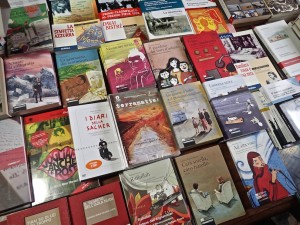

The fourth room is perhaps the most moving: it houses a carefully preserved bed sheet on which a country woman wrote the story of her love for one man, her husband, after he had died. She had already written volumes about life in her village and the surrounding country, and had run out of paper. So, as a memorial to her husband, she decided to write on one of their sheets. To help readers find their way, given the width of the sheet, she numbered every line, at each end. Some of this story is in the form of poetry. A beautiful book of this writing has also been published: Clelia Marchi Il tuo nome sulla neve (Your name on the snow). In fact, many of the diaries are available in published form – lovely books, at very reasonable prices (how do they do it?!).

We would like to thank Natalia Cangi and Alessia Clusini for their generosity, and for making this, our last day in Tuscany, so special.

Ann, with Murray Cox (who made the video)

Thanks, Ann and Murray. This is inspiring.