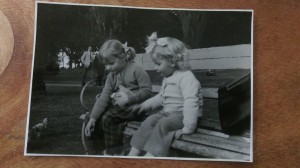

When my father-in-law died, after many years of sickness and many months in hospital, his wallet was in the drawer of the bedside cabinet. And in this wallet was a photo of his two daughters. Aged around 5 and 3, their hair in ribbons and pigtails, Anita and Ina are sitting side by side on a bench in a Sydney park, their feet unable to reach the ground.

When my father-in-law died, after many years of sickness and many months in hospital, his wallet was in the drawer of the bedside cabinet. And in this wallet was a photo of his two daughters. Aged around 5 and 3, their hair in ribbons and pigtails, Anita and Ina are sitting side by side on a bench in a Sydney park, their feet unable to reach the ground.

Both are so engrossed in what they are doing that they have forgotten the camera. With a look of solemn responsibility, the older sister is leaning forward with her right hand to offer breadcrumbs to the crowd of pigeons at her feet. The younger sister is captivated by the pigeons but also a little frightened, wanting to simultaneously lean forward and pull back. Her right hand is a blur of movement: perhaps she has just thrown down all her crumbs in one go. If so, she will have to ask for more because the older sister’s left hand has a tight proprietorial grip on the bag of supplies.

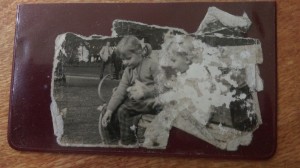

Karl carried this photo for over 40 years. It was ragged with age, and, like his wallet, curved from years of fitting in his back pants pocket. Some days, I imagine, the significance of the photo stopped him in his tracks, its impact as fresh as when he was initially moved to put it in his wallet; other times he must have seen it and merely recognised its existence; most days he must have looked right past it while reaching for banknotes. Even on the days he didn’t notice it, though, it must have mattered to him that he knew where it was, even when he was in hospital.

Karl carried this photo for over 40 years. It was ragged with age, and, like his wallet, curved from years of fitting in his back pants pocket. Some days, I imagine, the significance of the photo stopped him in his tracks, its impact as fresh as when he was initially moved to put it in his wallet; other times he must have seen it and merely recognised its existence; most days he must have looked right past it while reaching for banknotes. Even on the days he didn’t notice it, though, it must have mattered to him that he knew where it was, even when he was in hospital.

***

John Berger talks about such a photo in a poem called And our faces, my heart, brief as photos.

When I open my wallet

to show my papers

pay money

or check the time of a train

I look at your face.

This verse implies two photos and two ways of seeing. First, there is the photo on the passport papers. This photo identifies Berger, from the outside: he can prove he is himself when the flesh-and-blood face that is, the one directly in front of the customs officer, is the same as the representation of the face that was, in the year of the passport photo. For the customs officer, the truth about the living changing ‘John Berger’ only exists when it can be tied down, fixed to an old photograph. For the busy Berger, likewise, the customs officer, bank teller and train attendant are probably reduced to being no more than customs officer, bank teller and train attendant.

But there is at the end of the verse another face, ‘your face’, in a photo in a wallet, seen while Berger is hurrying through his daily chores. The archaic way of putting the last line of Berger’s verse might be ‘I behold your face’, and this captures well the sense in which Berger immediately feels beholden to this face. Although he has hurried past the bank teller and train attendant, his beholdenness to ‘your face’ stops his sentence. But this ending is not so much a closure as an opening, a hiatus where time and life change form.

Rather than the living face being reduced to the photographic face, this photo of ‘your face’ comes alive under Berger’s gaze. This is the living face of the nameless person who can hear Berger address them particularly through this poem, as a ‘you’: it is a particular person, and, from the tone of voice, someone intimate, but that person is never identified and in that sense could be any of us.

Berger doesn’t tell us what he sees when he looks at the photo. That is because you don’t see someone in the customs officer way if you’re directly talking with them. Just as in such a conversation, where what you say and thinks is changed by what the other person says and thinks, Berger sees with this face. And what he sees, evident in his beholdenness, is the relation that holds his ‘I’ and this ‘you’, even when they are apparently apart, even when he is busy with errands.

Rather than Berger fixing the face in a past, when the photo was taken, the face opens his imagination, and imagination doesn’t care about past, present or future and doesn’t care if he is at the train station or the bank. The poem goes on to tell us that what comes to his open mind is a fact. It is the sort of scientific fact that sticks in your mind like found poetry. It is the fact that the pollen of a flower can be older than a mountain. And what might this have to do with the face?

The flower in the heart’s

wallet, the force

of what lives us

outliving the mountain.

As I understand this, Berger sees in this face the force of life, or perhaps love: the eternity that is present in every moment, the potential that is simultaneously the past and the future and the present.

I don’t think Berger is at this moment deflecting from the ‘you’ of the photo, to make some general cosmological point. The photo has grabbed him, so that he can see more clearly than usual. What we have is not generalisation but concentration. What moves him is not vagueness but a fierce respect of facts. He is not therefore ignoring any of the detail that the customs officer would insist upon (hair colour, age, shape of nose), but his sight doesn’t need to latch onto these, as if they were the essence of ‘you’. What he sees, then, is the simple living truth of ‘you’, which is now also the truth of his ‘I’, and this truth is the blooming that is life. Everything in ‘the bigger picture’ is present, right here and right now, in the moment Berger says ‘I look at your face’.

***

Berger doesn’t say why the photo was in his wallet in the first place, and it is possible, although unlikely, that the photo had previously meant nothing to him. I can no longer ask my father-in-law why he put the photo there. And even if I could, he might not be clear on his motivations. But I have similar photos of my children, one in my office, pinned to my noticeboard, and a framed one in my kitchen, on a shelf above the coffee machine. In the former my sons are ages 3 and 5, in the latter ages 7 and 9. What do I see? What am I trying to remember? If I understand what might have drawn Karl to his photo, I will have a better sense of why my photos matter to me.

Opening Karl’s wallet, I find three sorts of thing: cash, public documents and private documents. There is not much to say about the cash: it gave Karl the power to buy things without needing to prove who he was. The public documents — credit cards, driver’s licence, membership cards, administrative identity cards — allowed the Karl to connect to the bureaucratic files in his name. They were keys to his civic existence, without which he didn’t have the identity to go about his daily chores. Doubtless Karl was particularly proud of his identity as a father, but I don’t think he carried the photo of his daughters as a proof-of-identity. I never saw him show it to strangers and, being homemade, it opened no official doors.

Finally, Karl’s wallet held small documents mediating his relations with himself: mementos, lists on yellow sticky notes, business cards carrying details he thought he might need but forget. I think this was the category to which the photo of his daughters belonged. I don’t mean that his young self thought his older self would need a photo to remind him that he had daughters; I mean that young Karl put the photo in his wallet to send counsel to his middle and old age. Whenever and wherever it popped up, the photo was intended to disrupt Karl’s everyday busyness and require a moment of reflection and respect that would reorientate his world and life. It was designed to bring him from his chores into the real world.

I think Karl felt the urge to put this picture in his wallet during an experience of being moved by it. It was this movement that made him realise his need for counsel: knowing that he had not in the past lived up to the demands of this photo, he must have felt he would lose his way again in the future. So it wasn’t just his daughters who were to be remembered: he wanted to be reminded of the revelation about his daughters that came through this photo. And he wanted this because the experience wasn’t an affirmation of something that he already knew. He wanted to be reminded that this photo had mysteriously overturned his identity and shown him a truth that he couldn’t trust himself to remember in a world filled with bank tellers and identity cards.

So what could this truth have been? What might Karl have seen? John Berger’s distinction between two ways of seeing will help me explain my guess. In one way, we note the identity of the subject of the photo, by ticking off attributes. This is an interpretation of a photo. I am outside the photo, looking at it. In this mode, Karl might see, perhaps, ‘Anita and Ina, my daughters, five and three years old at the time, feeding pigeons in Hyde Park in winter’. In the other way of seeing, which occurs unpredictably, I see with or through the photo: something about a photo catches me off guard and comes alive within me. No longer seeing the subject of the photo as a thing, I feel in the presence of their life, I experience their unselfconscious essence.

When Karl took the photo from his wallet he knew it depicted five-year old Anita, but, if the photo came alive, that wouldn’t be what he saw through it. The photo would allow him to see and feel a quality of who this amazing person is, whatever her age. It would produce clarity and not nostalgia and this effect would not derive from physical likeness. Etymologically, essence is is-ness, not the identity of a thing but the be-ingness of a being. The word spirit is also used for this essence. Without implying any supernatural element, I think Karl saw the spirit of this being that is his daughter.

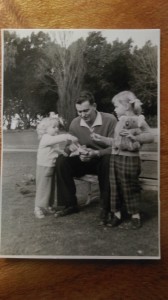

My guess is that Karl put the photo in his wallet as a grateful promise never to forget a moment of clarity when saw his daughters truly: their spark, their blooming, their potential, their relation, their vulnerability, their mortality. He saw the liveliness of life, flowing because of the connectedness of him and his daughters and the pigeons. He saw that the universe is in Sydney and that it is universal life that he witnesses in his daughters’ be-ing. And in this way, through them, he also saw, as he had never seen before, the life of his life.

I would reduce the fundamental mystery of his experience if I said the photo identified Karl’s life or Karl’s love for his daughters. What he saw was that this relationship was boundless, way beyond what he could have ever imagined. He was as much the product as the source of love, as much the product as the source of his daughters’ lives. He felt most alive and most himself and most present to his daughters when he felt that he-and-they were universal, the unfolding of life itself. He was most aware of the wonder and uniqueness of his daughters when he saw in them all children, all parents, the life of all life.

I would reduce the fundamental mystery of his experience if I said the photo identified Karl’s life or Karl’s love for his daughters. What he saw was that this relationship was boundless, way beyond what he could have ever imagined. He was as much the product as the source of love, as much the product as the source of his daughters’ lives. He felt most alive and most himself and most present to his daughters when he felt that he-and-they were universal, the unfolding of life itself. He was most aware of the wonder and uniqueness of his daughters when he saw in them all children, all parents, the life of all life.

Having been blessed by this vision of his relation with his daughters, Karl felt obliged to live accordingly, and this was the urge that prompted him to put the photo in his wallet. I think he was scared of how easy it is to live as if you’ve lost sight of what most matters about your life and those you love.

With his awareness of good fortune, young Karl would not have been expecting his older self to immediately see the photo as he had. Karl could pass on to his future self the promise of a mystery but not pass on its answer. If the vision came to the older man, it would have to come as a gift again, clear and wordless. The knowledge that this photo had once had significance, however, would warn the future self against dismissing it as something readily identified.

With his awareness of good fortune, young Karl would not have been expecting his older self to immediately see the photo as he had. Karl could pass on to his future self the promise of a mystery but not pass on its answer. If the vision came to the older man, it would have to come as a gift again, clear and wordless. The knowledge that this photo had once had significance, however, would warn the future self against dismissing it as something readily identified.

In sending into the future a photo that had once had great significance, Karl was sending a promise of the unnameable potential hidden between the things of the ordinary world. He was sending a warning about the danger of focussing on the things and thereby losing sight of this potential. In John Berger’s phrase, this life, this potential, this blooming is ‘the flower in the heart’s wallet’.

Andrew